So, you clicked here, did you? Well, good for you…sort of.

Let me start off by making a disclaimer or a full disclosure (can anyone tell me if there's a difference between the two?). First, this post is a little long. Second, you may not agree with or like everything I'm about to say. Third, I'm writing this because I actually care about writers like you, or at least that's my honest-to-goodness reason for hammering out this post. Fourth, and related to all of the above, I probably need to hear it as much if not more than you.

Okay, enough of the preliminaries. I thought I might grab your attention with my catchy title (you often have to pat yourself on the back when you're a writer, because your publisher, editor, agent, and readers aren't always up for it). Then I figured I'd offer my insights into what you should really do when you're having a hard time writing, whether it be from writer's block, fatigue, lack of inspiration, or the itty bitty shitty committee that lives in your head and tells you that your writing sucks.

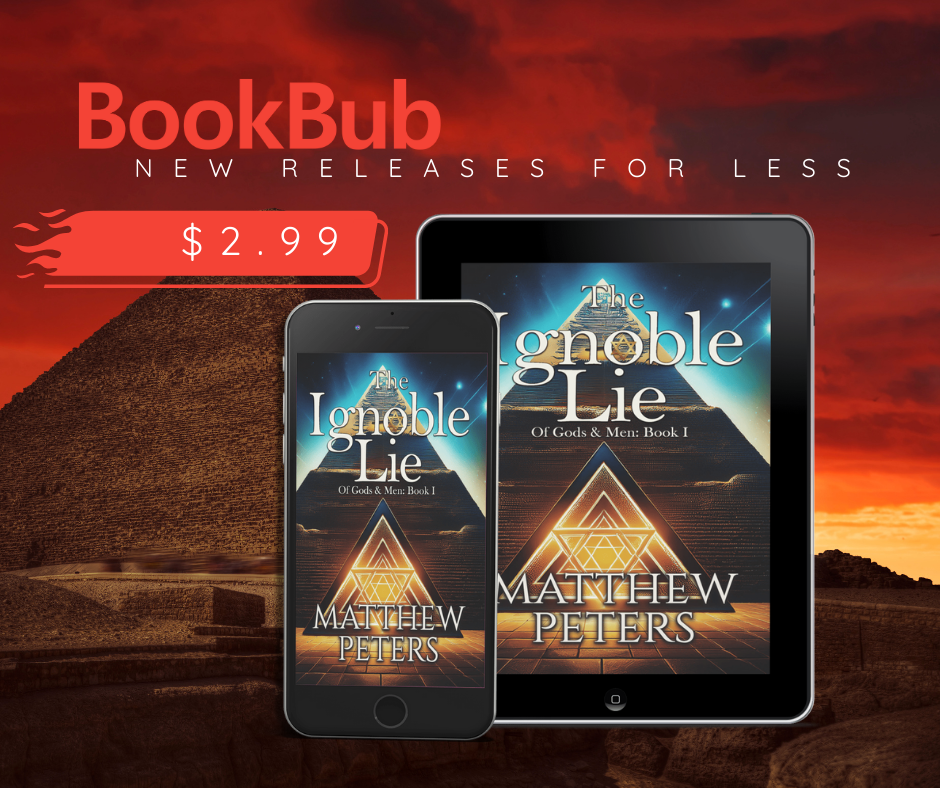

But wait! you might protest. Why take advice from a guy who has only one book on the market? Well, let me say a few things in my defense. First, there are thousands of writers out there (a rather conservative estimate) who give advice and/or publish how-to books on what to do when you're stuck in your writing who haven't many published books to their credit. So let's just say I'm in ___________company (I'll let you fill in the blank).

In fact, I've read so much of this advice and so many of these books (in case you're keeping track, this is the second point in my defense), that I feel warranted—no, I'd go with "darn near compelled"—to say something on the topic. Yes, friends, from Aristotle's Poetics, E.M. Forster's Aspects of the Novel (rewind if you missed the quantum leap) and Brenda Ueland's If You Want to Write, to more recent stuff by the likes of Dwight Swain (Techniques of the Selling Writer), Larry Brooks (Story Engineering), James Scott Bell (Plot & Structure), Ann Lamott (Bird by Bird), Natalie Goldberg (Writing Down the Bones) and a slew of others, I've read the gamut of writing books. So maybe that puts me in a place where what I have to say on the topic at least qualifies me to…well, at least not to say anything too stupid.

I know, I know. You're saying, "Well hell, Matthew, you've already gone and done that," to which I'd heartily concur and slap my head in Homer-Simpson-like fashion ("Doh"!). Nonetheless, I remain undaunted in my effort to (eventually) get to the point. Now I hear your chorus of, "Oh, please, God, soon!" so I'll make this a little shorter than I'd intended.

My ultimate point is this: If you're having a hard time writing, the best solution I can offer (after years of reading about writing much more than I've actually written) is to write. I've discovered via that long and winding road (and strawberry fields forever, man) that when you're a writer, the answer to most questions/issues concerning writing can be found by doing one thing: writing. Now, if you're completely burned out (and only you can tell if you are), or forcibly restrained, this does not hold, I repeat: this does not hold. But short of these exceptions, the general rule seems to be that, when in doubt, write. In fact, when you're not in doubt, write. Actually, I think there are only two times when you should write: when you feel like it, and when you don't. Even if you don't actually use what you write in your work in progress (WIP), having something on paper, to me at least, sure beats having nothing on paper.

But what if you simply can't write? What if all the gods, fates, and furies have combined to still your pen (or keyboard tap)? Toss concerns about a daily writing quota out the window and take the one-word challenge. What is that, you might ask? Just what it says it is: challenge yourself to write the next word in your WIP. That's right, just one word. My sneaking suspicion is that the one word might lead to another (but don't tell yourself that or you might freeze up). Try this. You might be surprised at the results.

At the end of the day, am I telling you not to read books on writing? No. I would never tell you to do or not to do anything. There are certain books out there I've found essential to keep me sane as a writer and a human being, and that help prime the pump when my creative juices freeze into a popsicle. If you're wondering what those books are, please see the books I mentioned earlier (maybe with the exception of E.M. Forster's book—I just couldn't get that one to work). Are there other good books out there on writing? Certainly. I just mentioned the ones that I can't do without. Your choices may be different. But I also know that writing books on writing is to some people a lucrative business, one that preys on our insecurities. So I think we need to be selective in the books we choose to help develop our craft, and to realize that, once we've got the fundamentals of writing down, often the solution to our writing problems is to keep on writing.

There are a million excuses not to write, but the creativity we use in coming up with such justifications and rationalizations would be better served furthering our WIPs. So the stark naked realization I've come to is that 99 out of 100 times, writing is the best solution to my writing problems. The boldness, starkness, and simplicity of this statement may catch some unaware or cause others to say, "Well, of course"! It's kind of like saying the answer to your smoking addiction is to stop smoking, and the solution to your drinking problem is to quit drinking. But ultimately, these ARE the answers, and, however simple and painful they are, they exist whether we want to acknowledge them or not. It's taken me a long time to realize this, and a longer time to implement it, so I needed to put it out there. I hope it helps someone.

I'll sign off with the words of Brenda Ueland. They've often provided me with the inspiration to keep writing and to remember that writing can be joyous:

You should feel when writing, not like Lord Byron on a mountain top,

but like a child stringing beads in kindergarten—happy, absorbed and quietly

putting one bead on after another.

All the best,

Matthew